The Chronicle

Gibson Mhaka, Senior Reporter

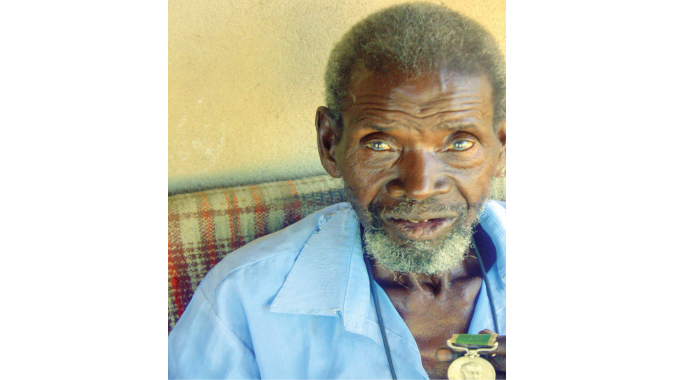

IN the heart of the rugged terrain of Gokwe North’s Matambo Village under Chief Chireya, a 90-year-old man sits comfortably on an old and torn sofa.

As he sits on that worn-down couch in the heat of a Gokwe morning, there seems nothing particularly remarkable about this old man or his surroundings.

However, as soon as he opens his mouth and starts recounting a heart-stopping tale of his past life, a life that brought him lifelong friendship with the man that would be Zimbabwe’s first citizen, it is clear that this is no ordinary man.

Mr Shepherd Madanhire, born on March 9 in 1932 and a former prison guard who served under the Rhodesia Prison Service recounts how he risked his own life smuggling letters from political prisoners like President Mnangagwa.

President Mnangagwa and other prisoners of his ilk were at that time classified by the regime as “most dangerous terrorists”.

Mr Shepherd Madanhire

Mr Shepherd MadanhireThey were isolated from other prisoners in a special section of single cells and automatically placed in “D” category.

They were the proverbial bad apples that the regime feared would spoil the bunch if they were allowed to mingle with other prisoners.

What he did not realise at the time was that he would one day give to an independent Zimbabwe, his incontrovertible and first-hand encounter with valiant defenders who took up arms to throw off long years of oppressive Rhodesian’s rule and achieve the ultimate goal of independence.

And it’s not often you have the opportunity to hear about the life of a larger-than-life individual like President Mnangagwa directly from the lips of one of his prison guards at Khami Maximum Security Prison (now Khami Prison) where he was incarcerated.

The President had been arrested in Salisbury’s Highfield township in 1965 for being part of the Crocodile Gang that carried out sabotage activities against the Rhodesian regime after receiving military training in China.

Mr Madanhire and ED first met around 1967 when ED was serving a life sentence at Khami Remand Prison.

A Chronicle news crew last week visited Mr Madanhire at his rural home about 124 kilometres from Gokwe town and he shared part of the story of President Mnangagwa’s long years behind bars while serving a life sentence for contravening Section 37 (1) (b) of the notorious Law and Order Maintenance Act.

“It was around 1967 when I came face-to face with a young Emmerson Mnangagwa. I was a prison guard at Khami Maximum Security Prison where he was serving a life sentence.

I met him through one of my relatives Ishmael Dube who was also a political prisoner there. The two – Emmerson and Ishmael were friends.

“When I first met the young Emmerson Mnangagwa, I was immediately taken by his ready smile and the gentleness in his eyes. He was down-to-earth and courteous,” said Mr Madanhire as he leans forward for emphasis.

An elder with an encyclopedic knowledge of all landmarks in the Rhodesia Prison Service, Mr Madanhire said he had too many stories to tell about President Mnangagwa adding that the President’s experiences at Khami Prison deserve to be in a book.

“Not many prison officers during that time can say they shook hands with him. Very few have encountered him personally since he was classified by the regime as most dangerous,” he said with pain scribbled all over his face.

“I saw his suffering and near-desperation when I used to stand behind him during the few visits his relatives were allowed and I could also see the anguish in him each time I talked to him or deliver a letter from his relatives and friends.

After a while, even though he was a political prisoner, a friendship grew between us. It was a friendship behind bars and I never dreamt that one day he was going to be the country’s President”.

He also details how he came to do “favours” for President Mnangagwa, smuggling his letters from prison which were apparently demonising the colonial regime and post them.

Mr Madanhire broke the rules to allow President Mnangagwa to communicate with relatives while he was behind bars.

“One of the cruelest rules was that prisoners should never write or receive letters containing subversive statements.

Inmates were initially prohibited from writing about prison conditions. But he (President Mnangagwa) could write and receive such letters through me. At times he was worried that I would get caught and be punished.

“It was quite a risky exercise and I didn’t want many people to know about this.

It was also one of my main duties to censor the letters that were being written by political prisoners. I was also accommodating his relatives at my house whenever they came to visit him,” explained Mr Madanhire.

“I would also smuggle newspaper cuttings into cells of these political prisoners so that they could read about the liberation struggle,” he added.

Mr Shepherd

Mr ShepherdMr Madanhire said many ex-political prisoners who were serving their jail sentences together with President Mnangagwa remembered him from their time inside as one of those rare phenomena: a prison officer with a heart.

“Other political prisoners I remember very well who served during the same time with him (President Mnangagwa) are Boniface Madzimbamuto, John Mashakada, John Mukoko, Saunders Mahwite and Ishmael Dube who I said was his close friend,” said Mr Madanhire.

He said he also connected a lot of political prisoners to some charitable organisations that helped them pay for their studies.

Mr Madanhire who retired in the late 70s, showed off a medal he was given upon his retirement from the Rhodesia Prison Service. Apparently, it is one of his most prized possessions.

He said before he retired, he had asked for a transfer from Khami Prison to Chikurubi Maximum Prison after one of the prison officers discovered that he was allowing letters from political prisoners to pass without being censored.

“This was after one of the prison guards stumbled upon a letter from one of the political prisoners asking for assistance. I quickly asked for a transfer to Chikurubi Maximum Prison before the matter was reported to the white officers.

“Despite the fact that we had created such a good relationship with the young Emmerson Mnangagwa it was unfortunate that I didn’t bid him farewell since my job and life were now at risky. Until now I have never met him,” he said.

“My long-cherished wish is to meet him. It really would be nice to meet him (President Mnangagwa) so that we go down memory lane”.

He also spoke proudly about the sense of solidarity he felt with political prisoners he was assisting at the time.

“I was institutionalised,” he says. “Even after retiring, I’d find myself looking at my watch and thinking, ‘I have to write up my report now and meet the comrades in their tiny cells.’ It took ages for it to sink in that I was no longer a prison guard.”

He also narrated how the Smith regime was ruthless to political prisoners with some being hanged in barbaric fashion.

“The smith regime was very ruthless. Political prisoners like President Mnangagwa were ill-treated. The living conditions were terrible and the cells were too small and we would allow them outside early in the morning for very few minutes for exercises and bathing.

“During those few minutes they were also expected to clean their toilet buckets. This is one of the reasons I risked my life smuggling letters for these political prisoners who were so determined that one day they will fight away white rule in the country,” said Mr Madanhire.

He said although he was a prison guard, he loved politics.

To show that he is a decades-long admirer of President Mnangagwa, Mr Madanhire also showed off the poster of President Mnangagwa for the 2018 Harmonised Elections which was hanging on the walls of his living room.

Mr Madanhire seemed to have resigned to the fact that life is a just a clock that is counted down until one finally gives up and breathes his or her last. His wife Herena died in 2005. Four of his eight children are also late.

The old man lives with his grandchildren.

Article Source: The Chronicle