The Chronicle

ON Monday night, cricket’s dark and murky side once again came out in the night like an owl.

After the cricket world celebrated a phenomenal series between South Africa and India, which followed the one-sided yet intriguing Ashes campaign, the game’s hidden secret once again garnered headlines around the world.

A little more than two decades after Hansie Cronje’s disturbing fall from grace, match fixing reared its head to send shockwaves throughout the world.

Hansie Cronje

Hansie CronjeIts latest target, former Zimbabwe captain Brendan Taylor.

Monday night’s revelations were equally shocking as disturbing, with the former wicketkeeper batsman once the glue holding the proud African nation.

In his troubling statement via Twitter, Taylor admits to falling into cricket’s trap.

“I’d fallen for it. I’d willingly walked into a situation that has changed my life forever,” he wrote in a statement.

Former England captain Michael Vaughan was one of the many cricket identities to react to the sad situation.

“This is so sad,” he tweeted. “I hope he can find a way to get better.”

Yet, this sorry tale is not the first and, certainly, it would seem, not the last.

Here is a road map to cricket’s sorry legacy.

The call that sounded alarm bells

If it sounds good to be true, it probably is.

Twenty-two years ago, cricket applauded a bold piece of captaincy from South African captain Cronje.

After days of rain, their home Test against England appeared all but over.

That was until Cronje approached his counterpart, Nasser Hussain, and asked whether both teams would declare and leave England requiring 248 runs in a little more than two sessions.

England would go on to win the Test by two wickets. Hussain, oblivious to the ulterior motives, showered his counterpart in praise.

“I hope Hansie gets the credit he deserves,” he said.

Cronje did.

Papers around the world called it “a triumph for all too rare positive thinking” and “brave, positive and brilliant” in another.

Yet, eyebrows were raised at Lord’s, the home of cricket, for his move, which went against tradition.

Even Cronje’s teammates were left aghast.

“I must be honest, I thought it was a terrible idea,” Mark Boucher wrote in his autobiography Through My Eyes.”

(Jacques) Kallis also thought it was wrong and so did (Lance) Klusener.

The feeling among the junior section of the dressing room was that Test matches are never, ever to be messed with.

You never give your opponents a sniff of victory in Tests unless you are desperate to win yourselves.

There was a simmering atmosphere of anger.

The truth eventually came out three months later, when Delhi police revealed they had recordings of Cronje conspiring to fix matches with an Indian bookmaker.

Three months further down the road, Cronje confessed and revealed he had sold the Test for £5 000 and a leather jacket.

A mere nine months after the infamous Test, Cronje was banned from cricket for life and another two players, Herschelle Gibbs and Henry Williams, banned for four months after accepting their captain’s offer.

The Cronje ordeal was meant to be a stake in the road.

In reality, it was merely just the start of a murky, dark relationship with bookmakers, one that has only been clouded because of the rise of T20 cricket and franchise leagues across the globe.

Cronje was not the end; he was merely just the beginning.

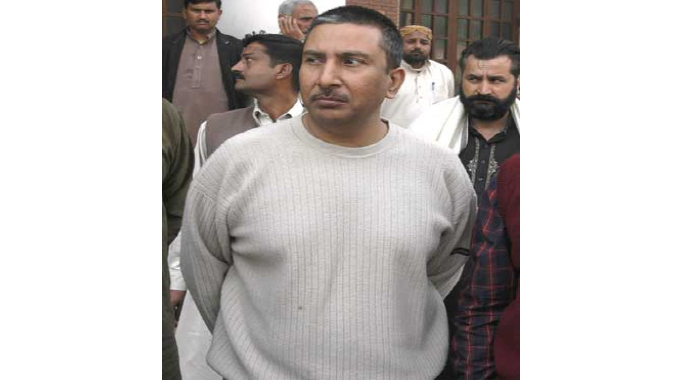

On May 24, 2000, the Qayyum Report was finally released.

In it, life bans were recommended for Pakistan great Salim Malik and Atu-ur-Rehman. Malik was also to be fined a million rupees.

Mushtaq Ahmed and Wasim Akram, one of cricket’s greatest players, were given the benefit of reasonable doubt, although it was recommended that neither ever captain Pakistan again.

Smaller fines were also handed out to Waqar Younis, Inzamam-ul-Haq, Akram Raza and Saeed Anwar for failing to co-operate with the inquiry. Malik slammed the findings.

“Why me alone when others have been let off with minor fines? Whether my cricket is finished or not, I have to live a life and I have been subjected to such tortuous allegations for a long time now, it is unjust,” he said.

Shane Warne recently accused Malik of offering him and Tim May $276 000 to underperform in a Test against him.

Malik denied the claim.

“Whenever a former cricketer launches his book or biography or anything of that sort, he tries to make things controversial to get maximum publicity,” Malik told Paktv.tv.

Soon after, Mohammad Azharuddin and Ajay Sharma were banned for life and Ajay Jadeja and Manoj Prabhakar were banned for five years.

Mohammad Azharuddini

Mohammad AzharuddiniIn his report, Qayyum wrote: “To those who are disappointed with their fallen heroes, it’s been suggested that humans are fallible.

Cricketers are only cricketers.”

Off the back of the Qayyum Report, the ICC announced in June 2000 that it was hiring former Metropolitan police commissioner Sir Paul Condon to run a new anti-corruption unit.

“If anyone still hasn’t learnt a lesson from our cases, then he will be foolish.”

A decade after the Cronje controversy, cricket was once again rocked.

Not for the first time, Pakistan’s players were in the spotlight.

But this time, it was one of the fresh faces of cricket, Mohammad Amir, a young man destined to do great things after a sparkling start to his career, that had fallen foul.

News of the World exposed another spot-fixing scandal, with captain Salman Butt and fast bowling duo Amir and Mohammad Asif accused.

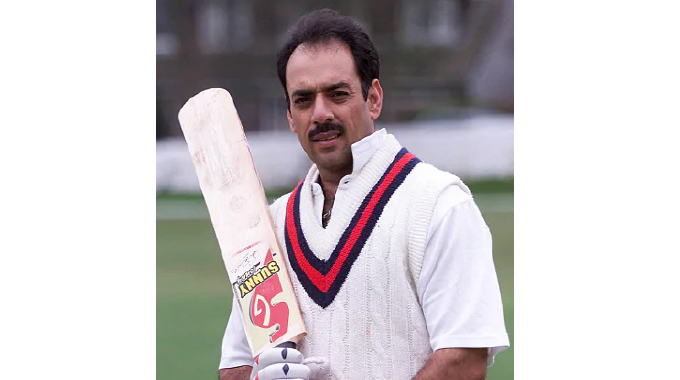

Mohammed Asif

Mohammed AsifDuring the fourth Test against England, Pakistan lost by an innings and 225 runs. Pakistan lost 14 wickets in one day and were bowled out for 74 in their first innings.

But it was the massive no-balls delivered by Amir that sent more alarm bells. News of the World revelations merely confirmed the world’s doubts.

All three were tried in a London court for offences under the Gambling Act and jailed in November 2011.

Butt was banned from international cricket for a decade, while Asif was handed a seven-year ban and a one-year prison sentence.

Amir, who pleaded guilty earlier than his teammates, subsequently received a five-year international ban and eventually returned to play for Pakistan once more.

“To be honest, I never thought about my comeback and I feel seriously lucky to play Test cricket again,” Amir told AP ahead of his comeback Test at Lord’s; the stage where his world came crumbling down.

“You call it a coincidence or whatever, but to me, it is a blessing that I am starting right from where I stopped in 2010.

I might have made my comeback months ago, but Test cricket is what I was looking forward to and this is my real comeback.

“I had missed five best years of my life and, had I continued playing cricket, everyone knows where I would have been standing today.

I have not forgotten 2010 . . . and I want to supersede my past with a better future.

I still hold those moments in my memory, but I want to get my name on the honour board at Lord’s once again.”

“If anyone still hasn’t learnt a lesson from our cases, then he will be foolish.

Corruption in cricket should not be allowed and anyone caught (in future) should be banned for life.”

The left-arm quick, who was the quickest in history to 50 wickets, made his return to Test cricket at Lord’s and played the last of his 36 matches against South Africa in 2019 before surprisingly retiring from international cricket.

Salim Malik

Salim MalikYou’re always living with a noose round your neck waiting to be bribed

Lou Vincent burst onto the scene by scoring a century on debut against a rock star Australian attack.

For many, it was the start of something special. But the New Zealand cricketer’s career would never reach those same heights again.

In 2014, seven years after playing his last international match, Vincent was found guilty of 11 counts of match-fixing.

Even today, he is not allowed to enter a cricket stadium.

After his international career came to an end and having hit a “wall of depression” he upped and left to the UK.

The same year the Indian Cricket League (ICL), a rebel T20 tournament, was launched in India.

Vincent decided to play the ICL to sustain himself. There, a bookie, posing as a bat maker, contacted Vincent.

It was not long until Vincent got sucked into the “honey trap”.

“He got straight into it,” Vincent said, recounting the incident.

“He said: ‘Listen, right, this is how the business works’ and he pulled out US$15 000 cash and set it on the table and said, ‘right that’s our down payment.

We deal in cash.

What we do is we bet inside games’.

And I was like, ‘oh sh*t’ – that’s when the penny dropped that I’d just been completely honey-trapped into a bookie.”

Ajay Sharma

Ajay Sharma“Because we had education, I had probably sat through about 12 seminars during my cricketing career, sort of warning us of this, but I was like oh, this is never going to happen to me, no chance it’s going to.

Then it was like, oh sh*t, I’m in trouble here.

He’s probably got cameras around the room recording what’s just happened and he’s given me US$15 000 cash, explaining how the betting system works and all that.

I was like, oh I’ve got to get out this room.

I said, ‘Listen okay cool, I’ll have a think about it.

I’ll go downstairs and have a think about it.’”

In his 2014 confession statement, Vincent had said he would regret his actions “for the rest of his life”.

During an interview on the Giving the Game Away podcast, Vincent added: “Once you’re there, you’re always living with a noose round your neck waiting to be bribed.

There’s always subtle conversations about your children and where you lived and things they knew about you that you didn’t even know.”

Vincent has attempted to turn his life around and has earned sympathy from his contemporaries.

The 43-year-old lives in Raglan, New Zealand, where he works as a builder and has constructed a little backyard practice area and pavilion which he has named the Windy Ridge Cricket Club.

Local families can use the area, and Vincent provides coaching tips.

‘Foolishly took the bait’

Monday night the world witnessed another cricketer’s world crumble down.

In reality, that world has crumbled around Brendan Taylor since the start of the Covid pandemic, which for most feels like years.

“I’ve been carrying a burden for over two years now that has sadly taken me to some very dark places and had a profound effect on my mental health,” Taylor wrote in a statement released on Twitter, foreshadowing a “multi-year” ban for a four-month delay in reporting a match-fixing approach

Taylor, who played 34 Tests, 202 ODIs and 45 T20Is for Zimbabwe from 2004 to 2021, admitted he took cocaine and a US$15 000 bribe from an Indian businessman in 2019, an interaction that caused his life to unravel.

The 35-year-old batsman said he was invited by an Indian businessman in October 2019 to discuss “sponsorships and the potential launch of a T20 competition in Zimbabwe and was advised that I would be paid US$15 000 for the journey”.

The invitation came when the team had not received salaries for six months and there were concerns the country would not be able to continue playing internationally.

He said he was a “little wary” but undertook the trip all the same.

During drinks on the last night, he was offered cocaine which the businessman and his colleagues were taking and said he “foolishly took the bait”.

“The following morning, the same men stormed into my hotel room and showed me a video of me the night before doing cocaine and told me that if I did not spot fix at international matches for them, the video would be released to the public,” Taylor wrote.

“I was concerned. And with six of these individuals in my hotel room, I was scared for my own safety.

I’d fallen for it. I’d willingly walked into a situation that has changed my life forever.

“I was handed the US$15,000 but was told this was now a ‘deposit’ for spot match fixing and that an additional US$20 000 would be paid once the “job” was complete.

I took the money so I could get on a plane and leave India.

I felt I had no choice at the time because saying no was clearly not an option.

All I knew was I had to get out of there.

“When I returned home, the stress of what had taken place severely impacted my mental and physical health.

I was a mess.

I was diagnosed with shingles and prescribed strong antipsychotic medication – maitriptyline.”

It took him four months to report the offence to the ICC.

“I acknowledge this was too long of a time but I thought I could protect everyone and in particular, my family,” he said.

– Foxsports.com.au

Article Source: The Chronicle