Source: The Moti Files: How businessman Zunaid Moti cosied up to the Mnangagwa regime

A trove of leaked internal documents has laid bare the close ties between controversial South African businessman Zunaid Moti and Zimbabwe’s highest-ranking politicians, bringing to light evidence of dubious multimillion-dollar transactions, a sustained effort to accumulate political influence, and apparent attempts to capture parts of Zimbabwe’s crumbling state.

Zunaid Moti is the owner of the Moti Group – a conglomerate with a diverse international portfolio including mining, property development and aviation.

The documents show he has enjoyed a close personal relationship with Zimbabwe’s president, Emmerson Mnangagwa, and its vice president, General Constantine Chiwenga, and repeatedly leaned on them when he needed help in business and personal matters.

Moti has rejected any suggestion that he or the Moti Group’s major chrome mining venture in Zimbabwe, African Chrome Fields (ACF), received undue or improper benefits because of their relationship with Zimbabwe’s government. He also denied that he, ACF or the Moti Group were involved in any form of capture of the Zimbabwean state, and claimed ACF conducts itself like any other international investor in Zimbabwe.

After being arrested in Germany in 2018 on a seemingly manufactured Interpol “red notice” in connection with a business deal gone awry, Moti turned to Mnangagwa and Chiwenga for help. His letters from prison reveal a man who, in his hour of desperation, was remarkably loose-lipped about his business dealings as he sought to urgently shuffle money around the world to pay for his defence and lobby for his release.

The letters also portray a boss who micromanaged the affairs of his sprawling business empire, especially ACF which enjoyed favourable concessions from the Zimbabwean state.

The Moti Group’s involvement with Zimbabwe’s political elite stretches back several years. In 2014 it gained a significant foothold in Zimbabwe with its acquisition of ACF.

Then, in November 2017, during the coup that ousted long-time ruler Robert Mugabe and brought his deputy, Mnangagwa, to power, ACF forged an alliance with another controversial and politically connected businessman.

Zimbabwean fuel tycoon and Zanu-PF benefactor Kudakwashe ‘Kuda’ Tagwirei, bought 30% of the chrome company for a formidable $120-million.

ACF became a conduit through which millions of dollars of this cash flowed into a diffuse money-moving operation that shifted cash into a myriad of entities in Zimbabwe – and possibly onwards to the South African side of the border.

The Moti Group describes these on-payments as investments and “loans”, made simply in order to try to protect the value of the sale proceeds from depreciating.

(Details of this extraordinary money-moving enterprise, enlisting well-known “informal” financial operators, will be revealed in Part Two of the Moti Files.)

Cash also flowed to various obscure companies, some of which appear to be linked to prominent Zimbabwean politicians, including Mnangagwa and his second in command, Chiwenga.

Neither Mnangagwa nor Chiwenga responded to requests for comment. The Moti Group denied that they made any payments to politicians.

See: Spincash Machine: Payments to the President’s Farm and Vice President’s Associate Followed a $120-Million Chrome Deal published by the Sentry, with whom amaBhungane is collaborating on this story.

Whether the deal and the payments were initially linked to Zanu-PF power struggles and the coup – either as a way of funding the coup or a means of externalising funds for those on the losing side facing indefinite exile – remains conjecture. The timing could be purely coincidental, as the Moti Group claims.

Moti denied “involvement in, or any other dealings related to or associated with the ‘coup’” and said that linking him and the Moti Group to the coup was part of “a nonsensical and false narrative aimed only at causing me reputational harm”.

Nevertheless, the documents offer glimpses of Moti’s unbridled ambition at work in, for instance, sweeping plans to rope the Zimbabwean government into state-backed ventures to centralise mining in the country and create a state-backed pharmaceutical company.

Though these particular plans ultimately faltered, others were successful.

The sheer extent of questionable business practices that the documents suggest, which lead right up to the most senior political post in Zimbabwe, go some way to explaining the Moti Group’s frantic attempts to plug the leak.

The Group has accused a former employee, Clinton van Niekerk, of having “stolen” the confidential information.

Van Niekerk was arrested at Durban’s King Shaka International Airport on 25 January as he was about to leave the country.

This sparked a legal showdown in which Moti’s former business partner-turned-rival, Frederick “Frikkie” Lutzkie, who had taken Van Niekerk under his wing, intervened with his legal team to secure Van Niekerk’s release.

Two days later a court set aside Van Niekerk’s arrest and he was released from custody in Johannesburg, where he had been taken under questionable circumstances and in defiance of a court order (see amaBhungane’s original report here).

The Moti Group has not given up on making an example of Van Niekerk and is seeking a court order setting aside the order for Van Niekerk’s release, though their former employee is now said to be in witness protection.

In a written response to amaBhungane sent via his lawyers, Moti maintains that the documents were “stolen” and that, by extension, amaBhungane is “knowingly perpetuating unlawful conduct”.

He warned, “Insofar as the matter is currently being investigated by the SAPS, I have instructed [my lawyers] to inform the SAPS of your involvement for purposes of potential further investigation and/or charges.”

Moti has cast doubt on the authenticity of the documents, saying that “any document you are in possession of cannot be relied on and could have been altered in any way” and “should be viewed as a possible forgery”.

Concerning his and the Moti Group’s ties to Zimbabwean political elites, Moti said that this was the “norm” in Zimbabwe.

“The commercial operating environment in Zimbabwe is such that all international investors have access to various officials and ministers as a norm, and the fact that ACF’s representatives interacted with politicians was not untoward and is standard practice in the country.”

Moti rejected any suggestion that he or ACF received undue or improper benefits because of their relationship with Zimbabwe’s government.

“ACF is an investor in Zimbabwe who is utilising the various programmes implemented by the government of Zimbabwe in order to invest in the country and gain some economic concessions by investing within the programmes. By investing as mentioned herein above, is not illegal nor is ACF doing [anything] untoward. It is certainly not capturing the state of Zimbabwe.”

See Moti’s full response here.

Old friends

The leaked documents show how the Moti Group was teed up to benefit from a drive by the Zimbabwean regime to claw back mining rights from existing holders.

In March 2015, Zimbabwe’s long-time autocratic leader, Robert Mugabe, visited ACF’s mine in central Zimbabwe where the company had plans to set up a smelting plant using “groundbreaking” technology.

Mugabe told those in attendance, “When we first heard about this new technology by Vice President Emmerson Mnangagwa, I thought maybe he just wanted me to come over to his former constituency. Today I’ve witnessed for myself this sophisticated technology that can smelt chrome in less than two minutes.”

Roughly a year later, the Moti Group struck a deal with a company called Rusununguko Nkululeko Holdings (RNH) to set up a joint venture to tap into the country’s rich chrome reserves.

RNH is owned by Zimbabwe’s military, which has been implicated in widely publicised human rights violations and has carved out lucrative niches for itself amid Zimbabwe’s collapsing economy.

In terms of the joint venture agreement, ACF would do the actual mining and processing of ore, while RNH would acquire the mineral concessions to mine and pave the way for ACF by obtaining permits and clearing regulatory hurdles.

At this early stage, the hand of then Vice President Mnangagwa was already detectable in the Moti Group’s Zimbabwean venture.

A clause of the agreement referred potential disputes to “mediation” by the “Principals”, namely “Honourable ED Mnangagwa on behalf of [the Republic of Zimbabwe]” and Moti on behalf of his group of companies.

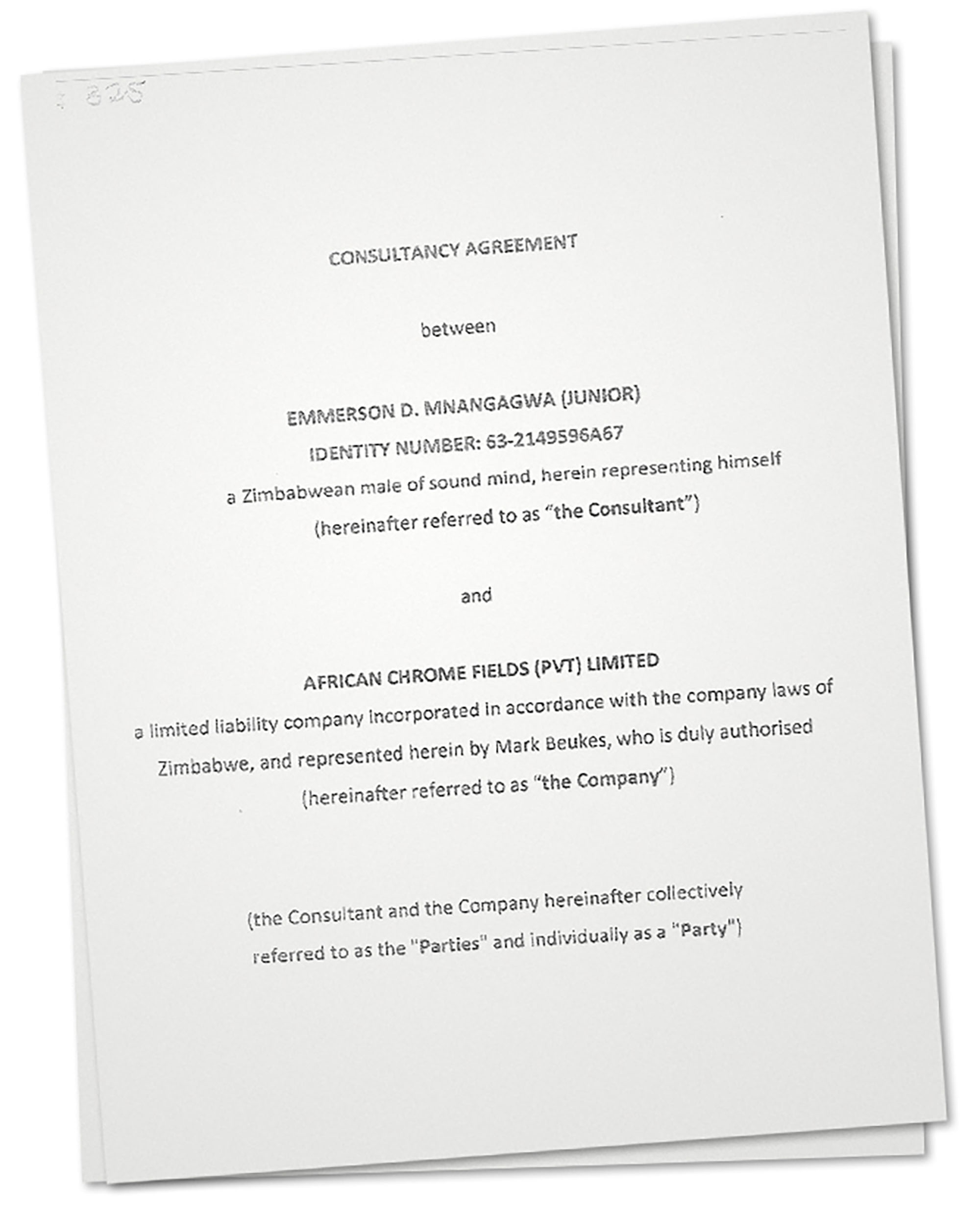

Mnangagwa’s son, Emmerson Mnangagwa Junior, was also given a role.

He was brought on board as a “consultant” for ACF the month after the joint venture deal was signed, and was hired to provide services such as “liaising with the Company’s stakeholders, including the Government of the Republic of Zimbabwe” and “planning and implementing an appropriate communication strategy for the company”.

For this, the younger Mnangagwa would be paid $5,000 per month, later doubled to $10,000.

An unsigned trust deed shows that the Moti Group planned to help Mnangagwa set up a trust for his and his family’s benefit, although Moti says Mnangagwa Junior “asked the company secretary working for the Moti Group at the time to advise on a draft trust deed” and the deed was never finalised.

Neither Emmerson Junior nor President Mnangagwa responded to requests for comment.

Moti told us, “At the time that ACF launched its operations in Zimbabwe, Robert Mugabe… was the President. ACF was new to the Zimbabwean landscape and operating environment and believed someone like [Mnangagwa Junior] could add great value in assisting with introductions to key stakeholders’ relations.

“It is concerning that you appear to create the insinuation that Junior was excluded from seeking employment simply because of the office held by his father. This is nonsensical.”

Moti also denied that there was anything improper in Mnangagwa Senior representing one of the parties in mediation between RNH and ACF.

In the wake of the joint venture agreement and after hiring the then-vice president’s son, the benefits to the Moti Group began to flow.

In May 2015 ACF applied for “National Project Status”, which it received later that same year, allowing the company tax exemptions on the import of capital goods.

The month after ACF submitted its application, Mnangagwa went to Cabinet with a proposal to lift an export ban on chrome ore that had been in place since 2011, according to a copy of Mnangagwa’s Cabinet memo contained in the Moti files. The lifting of the ban was announced days later.

Over the next couple of years, other benefits followed.

A letter signed by Moti, for instance, suggests that ACF was allowed to import chemicals duty-free. This allowance may have flowed from the company’s National Project status, which Moti points out was designed to attract investment and was enjoyed by other well-known companies.

In another example, ACF was permitted to “set-off” amounts owed to other Moti Group companies across the border in South Africa against its revenue – something Moti says was just to “facilitate ease of cashflow for operational purposes in the context of severe liquidity challenges”.

Moti kept up his efforts to extract favours from Mnangagwa. In a January 2016 letter, Moti sought the vice president’s assistance in getting the Finance Ministry to exempt ACF from fuel import duties.

In return, Moti pledged to “provide the Midlands Zanu PF Government with 10 000 litres of fuel per month, which fuel can be utilised by the Police and Army Forces in and around the area”.

Mnangagwa comes from the Midlands and it is his political stronghold.

In his letter promising fuel to the army and police, Moti went further, requesting Mnangagwa’s assistance in a matter involving a Moti Group executive’s luxury vehicle which had been impounded over a dispute with Zimra, the Zimbabwean Revenue Authority. Moti urged that the employee be “alleviated of this rather disturbing position he finds himself in with the assistance of yourself [Mnangagwa] and Zimra”.

Moti even threw in a request for Mnangagwa’s assistance in helping him obtain a diplomatic passport, ostensibly so that he would be immune from having to make disclosures at a South African inquiry related to supposedly sensitive mineral processing technology that ACF was using in Zimbabwe. It is unclear what inquiry Moti was referring to.

Moti told amaBhungane: “I did not, and do not hold a diplomatic passport from any country”, though he did not deny having requested one. He described his offer to provide fuel to the Zimbabwean police and armed forces as a “philanthropic” gesture to “support local government in the area in which ACF operates”.

Moti maintained that ACF acquired its various concessions legitimately through proper institutional processes, saying “ACF always applied for concessions through the relevant ministry, fully motivated and reasoned”.

“These applications went through vigorous review by various departments before being granted and were not unique to ACF, but are granted if justified, to many foreign investors in the country, in line with prevailing legislation at the time.”

He added that “some concessions were granted, and others were not”.

However, the documents amaBhungane has reviewed cast doubt on Moti’s claim to have always gone through proper channels, and point to direct and personal appeals to senior politicians – Mnangagwa in particular.

Many such requests, especially the more outlandish ones, were ignored or otherwise went unfulfilled, but by 2016, the vice president had become a key interlocutor in ACF’s relations with the Zimbabwean state, and ACF was not shy about its links to Zimbabwean political elites and the ruling Zanu-PF.

One 2016 overview document boasted about ACF’s “relationship with the Presidency” and the “interaction and support from related and associated Ministries and Parastatals”.

The same document noted that ACF’s joint venture with the Ministry of Defence gave the company “access to all claims currently owned by larger players”.

2016 saw further requests from the Moti Group for Mnangagwa’s intervention.

An April letter from Moti Group executive, Ashruf Kaka, to the vice president is typical of the Group’s routine interactions with Mnangagwa.

The letter referred to a prior meeting between the two men on 31 March 2016 and called for the vice president’s “urgent intervention, assistance and direction” in obtaining approval for a fuel rebate and assistance with VAT refunds.

Kaka proposed that if Zimra were unable to pay VAT rebates, “we humbly request that we receive a dispensation aligned with the National Project Status such that we are not required to pay VAT”.

In response to detailed questions, Kaka denied any impropriety in his relationship with the office of the Presidency and said that the mining and finance ministries formed part of Mnangagwa’s portfolio as vice president at the time. (See his full response here.)

Kaka told amaBhungane: “As ACF had [National Project status], it was [Mnangagwa’s] function to streamline all regulatory processes for ease of business where companies invested [foreign direct investment, or FDI]. This was aimed at troubleshooting difficulties experienced by foreign investors such that foreign investment in Zimbabwe was encouraged. This applied to all foreign direct investors who brought in FDI and was not exclusive to ACF.”

Moti said that “numerous countries, including Zimbabwe and South Africa, offer various incentives to investors to attract foreign direct investment, promote economic growth and create jobs”. National Project status, he added, was one such incentive that was granted to many other companies.

According to Kaka, the diesel rebate was a means of incentivising foreign investment, which did not amount to a “concession”. It was “granted by the Ministry of Transport by proclamation to mining operations in remote areas where electricity supply is virtually nonexistent”.

Kaka said that the request concerning VAT was due to Zimra’s “inability to make payment of VAT refunds due to ACF”.

“In essence, there was compliance by ACF in its payment of VAT and non-compliance by the Zimbabwean Government to process and pay refunds. As ACF had [National Project status], we requested that there be a set-off to enable efficient and effective cash flow for both Zimra and ACF…

“More importantly, this request was refused, which demonstrates a clear and unequivocal application of discretion used, which did not always favour ACF.”

Chiwenga, then head of the Zimbabwean armed forces, was not spared requests for help either.

A June 2017 memo to Chiwenga, prepared by Kaka, proposed that Chiwenga push for a prisoner swap with the UAE in order to secure the extradition of one of Moti’s enemies resident in the UAE.

Kaka and the Moti Group requested that an “exchange be arranged between UAE and Zimbabwe”, where the latter would hand over a certain UAE citizen detained in Zimbabwe in return for the UAE extraditing Moti’s long-standing rival, Russian businessman Alibek Issaev, to Zimbabwe – a “fair exchange”, as the document put it.

Kaka, in response, told amaBhungane that “I was informed by the office of the prosecutor in Zimbabwe that a UAE citizen was detained in Zimbabwe for some or other offence and that the UAE government were seeking his release.”

On Kaka’s version, the office of the prosecutor requested Kaka to “engage and present to VP Chiwenga (together with them) a request for a possible prisoner exchange”.

“This request was presented and after consultation that VP Chiwenga had with the department of justice, home affairs and other departments, the request was declined…”

Political patronage

ACF’s operations in Chirumhanzu-Zibagwe soon became enmeshed in the local Zanu-PF patronage machine. The Midlands district is Mnangagwa’s former constituency and the area his wife Auxilia represented as a member of parliament from 2015 to 2018.

In February 2017, ACF representatives sat down for a meeting with local Zanu-PF figures at the “ACF lapa”. Also at the meeting that day was an irate Auxilia Mnangagwa who “did not greet or acknowledge” the ACF team because of a failure to return a call to confirm the meeting.

The events of that day are described in an 11 February 2017 email from ACF’s chief technical officer, John Drummond, to Kaka.

According to the email, the meeting discussed an employment scheme at ACF involving the government and regional Zanu-PF office, in terms of which job seekers would register with the Department of Labour and receive a “coupon” proving their registration.

“The entire exercise was to ensure that only Zanu-PF members and pro-MP Mnangagwa supporters get jobs,” Drummond noted.

Keeping the local Zanu-PF and Mrs Mnangagwa onside appears to have paid off for ACF. Drummond stated in his email that “we had to provide the names of the workers committee, and MP Mnangagwa interrogated them and told them not to strike”.

Kaka told amaBhungane that he did not recall the email, but that “I have a recollection whereby I engaged the then [vice president] to advise his wife, Auxilia Mnangagwa, not to interfere in any way with plant operations directly or indirectly”.

He said to the best of his recollection this was her only visit.

Rifts

2017 was an important year for ACF, and an especially tumultuous year for Zimbabwe, culminating in the week-long November coup that replaced Mugabe with Mnangagwa.

The coup came amid factional infighting over who would replace the 93-year-old Mugabe, with one side backing Mnangagwa and another, the younger, so-called G40 faction, backing First Lady Grace Mugabe.

In the lead-up to the coup, ACF found itself in a difficult position with the Ministry of Mines and Mining Development, headed by Mugabe loyalist and relative Walter Chidakwa. Moti acknowledged that Chidakwa was “very destructive to the ACF relationship in Zimbabwe”.

It is unclear whether ACF was caught up in factional politics and this falling out came as a result of the company’s perceived closeness to the Mnangagwa faction, but in September 2017, just two months before the coup, Chidakwa’s Ministry informed the Moti Group of its refusal to reissue ACF’s export permit to allow it to export chrome ore.

The reason the minister gave for the refusal was ACF’s failure to meet its obligations for processing raw chrome locally. This, said the minister, was “in spite of the many benefits extended to [ACF] through national project status”.

It appears from the documents amaBhungane has seen that only after the Moti Group launched an urgent court application to set aside the minister’s “unilateral” decision did the ministry back down, issuing a new permit, though with far more restrictive terms than previously, and valid only for one month as opposed to the usual quarterly term.

Moti told us the minister held a personal animosity towards him and acted against ACF without good reason.

ACF’s partnership with RNH, the Zimbabwean military-owned company, was also becoming increasingly fraught. On 17 November, in the midst of the coup that had begun three days earlier, RNH addressed an angry letter to ACF, accusing the company of dragging its feet in getting the joint venture up and running. RNH accused ACF of having “exhibited insincerity” and demanded $1.2-million for what it said was ACF’s “illegal” exploitation of its mining concession.

Coup

On 21 November 2017, the coup ended when Mugabe was eventually convinced to resign, ending his 37-year rule. With Mnangagwa at the helm and Chiwenga as his deputy – the latter having led the armed forces during the coup – ACF’s fortunes suddenly seemed to change.

Chidakwa was purged from his position and arrested the following month on allegations of corruption, and before the year was over, ACF had secured from the new minister a permit for a full year. In terms of this new permit, ACF was now allowed to export 650,000 tons of ore – about two to three times the usual quarterly volume that previous permits allowed for.

The following year, ACF would also patch up relations with its partners in RNH. The former addressed a letter to RNH noting that the two sides had committed to “more effective communication”, and that ACF had sunk money into mining the military’s concession but that it did not appear to be economically viable.

November 2017 had heralded another major boon for the Moti Group when, on the 17th, as the coup was unfolding, the Moti Group signed a multimillion-dollar deal with well-known Zanu-PF benefactor Kudakwashe Tagwirei – a man Mnangagwa once described as his “nephew”.

The US imposed sanctions on Tagwirei and his company, Sakunda Holdings, in 2020 for “materially assisting senior Zimbabwean government officials involved in public corruption”.

The Moti Group’s deal with the Zimbabwean tycoon involved the sale of a 30% stake in ACF to Sakunda for $120-million (about R1.7-billion at the time) paid in installments through to mid-2018.

The 30% was technically held by a local Zimbabwean company independent of the Moti Group called Spincash Investments, though it was run by Moti Group executives and did not even have its own bank account.

According to documents amaBhungane has seen, from ACF a portion of the money was distributed to various obscure companies, with about $5-million ending up in companies identified with Zimbabwean politicians.

The new president’s family appears to have received a slice of the funds when $1-million went to Pricabe Enterprises, the company that reportedly owns Mnangagwa’s farm, on 5 December 2017.

Over December and January, $2-million was transferred from ACF to a company called Cosmotex Investments controlled jointly by Lishon Chipango, who held varying stakes in ACF via Spincash, and Evelyn Chakuinga, reported to be Chiwenga’s niece.

Chipango is reported to be Chiwenga’s “investment manager” and proxy.

On 4 July 2018, shortly before the 2018 elections, $1.75-million went to Spartan Security, which is partly controlled by Mnangagwa’s relative, Tarirai David Mnangagwa, who is reported to have helped Mnangagwa flee Zimbabwe after he was sacked by Mugabe days before the coup.

There is also circumstantial evidence suggesting that a major portion of the ACF-Tagwirei funds ended up in Moti Group companies in South Africa using a byzantine scheme of loans and investments. (More on that in Part Two.)

Prison

If 2017 was an eventful year for the Moti Group, the following one was even more so. On 19 August 2018, Moti was arrested in Germany as he was departing through Munich Airport.

An Interpol arrest warrant had been issued against him amid a wide-ranging, years-long dispute with Issaev – the Russian businessman Moti had tried to get extradited to Zimbabwe.

Issaev was Moti’s estranged prospective investor in the Moti Group’s South African chrome smelting venture, FerroChrome Furnaces. The deal fell apart amid mutual allegations and criminal complaints.

From the moment of Moti’s arrest in Germany, where he was held for five months until January 2019, there followed a torrent of correspondence between him and his associates as they tried to lobby for his release, mount an international legal defence, and shuffle money and assets around the world to pay for this.

From his prison cell, Moti kept a tight rein over his businesses, micromanaging operations in Zimbabwe by, for instance, enquiring about technical details of the chrome wash plants, giving instructions on cost-cutting, and enquiring about fuel cost calculations in letters that sometimes ran thousands of words long.

Among the first people Moti and his closest associates turned to in his hour of need was Mnangagwa.

On 30 August, Kaka wrote to the president “humbly” requesting his assistance in “facilitating” a meeting between himself and South African President Cyril Ramaphosa to discuss Moti’s arrest.

Kaka told amaBhungane: “It is correct that I requested President Mnangagwa to facilitate a meeting with myself and President Ramaphosa of South Africa, to assist in Moti’s release. Moti was arrested unlawfully and this was subsequently vindicated by his release and the Interpol release statement.

“At the time, the South African government, in my view, did not play its part in Moti’s release. No meeting took place between myself and President Ramaphosa as President Mnangagwa did not want to get involved in the internal matters between South Africa and its citizen.”

Moti told us, “I have shown that I was detained in Germany unlawfully, and that I was innocent. Now imagine if you found yourself in a similar situation. You are an innocent person being held in Germany, facing possible extradition to Russia where the authorities are notoriously brutal. Would you not ask any and all of your acquaintances for assistance?

“I have met and engaged with both President Mnangagwa and Vice President Chiwenga through the years I have actively invested in Zimbabwe. Facing extradition to Russia, I wrote to several influential figures including President Ramaphosa and Lord Peter Hain asking for any assistance they may be able to provide. There is nothing illegal about this.”

In another letter early on in his detention, Moti asked Mnangagwa to convince German Chancellor Angela Merkel to intervene in his arrest, writing: “Pls can you write a letter to Mrs Merkel of Germany requesting her input into this matter as I am a friend of the Zimbabwean people uncle.”

Moti questioned the authenticity of the letters and told us, “I don’t know what you base your assumptions on since you refuse to let me have sight of the documents, nor do you actually ask a question. You infer an improper relationship between me and President Mnangagwa, and state that the matter at hand was my imprisonment in Germany, but you base this on the flimsiest unconfirmed writings from unknown sources. In any event, I can confirm that President Mnangagwa did not write any such letter to Mrs Merkel.”

Yet Moti’s closeness to Mnangagwa and Chiwenga appeared to be on full display in his prison letters.

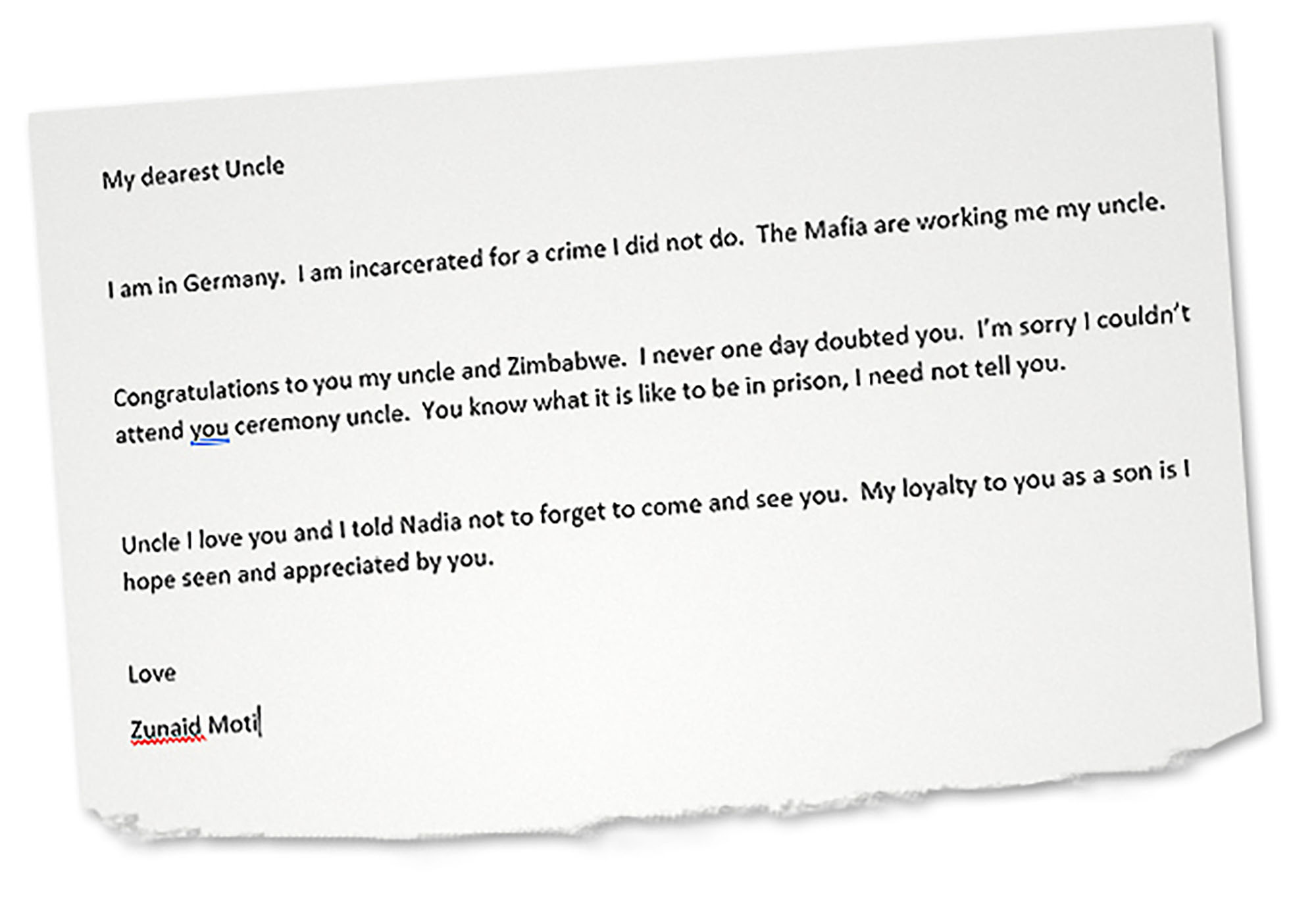

In one letter addressed to “uncle”, a term he often used to refer to Mnangagwa, Moti wrote in apparent reference to Mnangagwa’s inauguration: “Congratulations to you my uncle and Zimbabwe. I never one day doubted you. I’m sorry I couldn’t attend your ceremony uncle… Uncle I love you… My loyalty to you as a son is I hope seen and appreciated by you.”

Moti told us, “President Mnangagwa and I know each other and have a fondness for one another. If I wrote a personal letter to President Mnangagwa, then there is nothing illegal about this.”

To Chiwenga, or “Brother CDF” as he referred to him, Moti wrote: “Please call my father and go see him brother. Hold him tight and give him my love my dear brother. Do this for me. He, like me, loves you very much CDF.”

CDF appears to stand for “commander of the defence force”.

Moti’s attentiveness to the wants of his political patrons showed great attention to detail. At one stage he wrote, “I sent uncle and 2IC nuts. They love those roasted ones.” A follow-up letter of his read: “Feedback on 1 and 2. Nuts eaten etc.” If “nuts” was a codeword for something else, it’s unclear what.

Throughout the documents, “No1” or “Uncle” are used to refer to President Mnangagwa, while “No2” or “CDF” are used for his deputy, Chiwenga.

Moti has questioned this, saying that No1 could refer to the person in charge of ACF operations in Zimbabwe, and CDF could stand for “Chrome Development Foreman”, while references to Tagwirei as “Kuda” could in theory “be anyone” as it “is a common name in Zimbabwe.

But the correspondence between Moti and his associates provides contextual evidence as to who these names likely refer to.

There is, for example, an update from Kaka mentioning a meeting in September 2018, after which “No1 left for New York” – the same time Mnangagwa travelled to New York to attend the UN General Assembly for the first time as head of state. When an October 2018 letter from a Moti Group employee noted that CDF was “really ill”, Chiwenga’s illness was publicly reported at the same time.

Unguarded

Moti’s desperation is palpable in his letters, and in his moment of need, he was remarkably unguarded about what he put in writing.

In one letter that appears to have been digitally transcribed by one of his employees, Moti instructed his assistant to “take $30” (which may have been a reference to 30,000 US dollars, though this is unclear) to “No1” and “read my letter to him as well as let him see that I care for him and don’t forget him ever”.

Moti also instructed the assistant to “take $20” to CDF(2) – a reference to Chiwenga’s title as commander of the defence forces and number two to Mnangagwa.

Although the transcription is not entirely clear, one of Moti’s letters appeared to refer to “uncle” and CDF (in other words Mnangagwa and Chiwenga) as being “equity partners”.

Moti told us, “Again, there is no evidence that this letter has not been altered. ‘Uncle’ and ‘him’ obviously does not refer to the President and Vice President since they are not shareholders in any of the operations in Zimbabwe and have never been. Again, you assume that either of these figures are ‘hidden’ partners. They are not, nor have ever been partners in ACF or Spincash.”

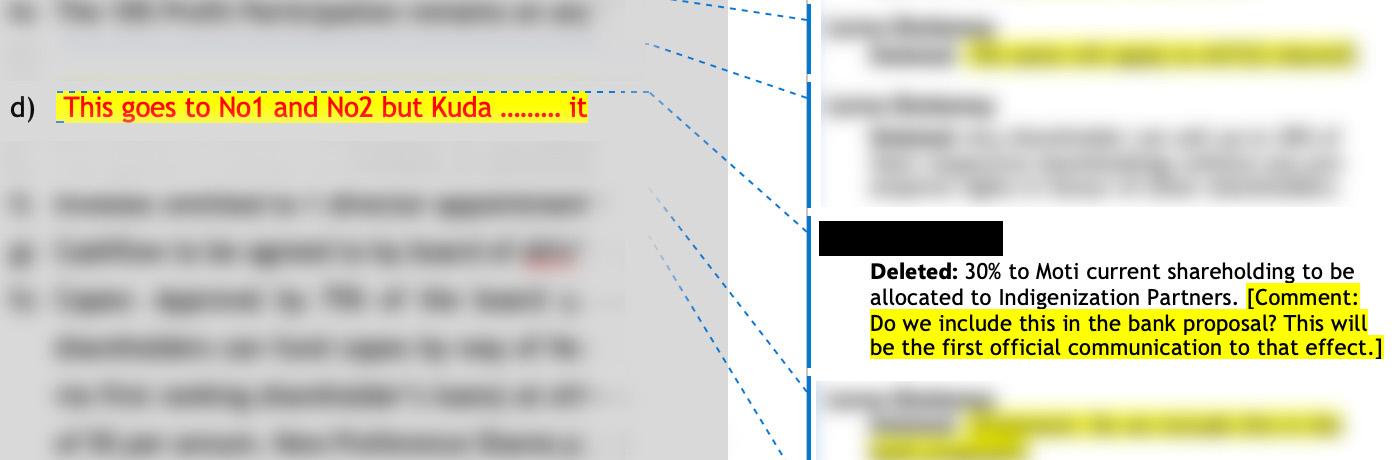

The two politicians’ possible interest in the Moti Group is alluded to in another document.

An October 2018 memo on the Moti Group’s debt to Investec Bank proposed, as part of an overall restructuring of the debt, to increase the Bank’s interest in the Group’s South African chrome marketing subsidiary, Africhrome, in which Tagwirei had rights to a portion of income.

The document is heavily annotated and edited and is likely a transcription of a letter on which Moti provided comments from prison. The metadata shows it was authored on his personal assistant’s computer.

Point “d” of the letter is particularly illuminating, as there is a deleted line that reads: “30% to Moti current shareholding to be allocated to Indigenization Partners”. Alongside that, someone inserted the following comment: “Do we include this in the bank proposal? This will be the first official communication to that effect.”

In a red font that appears to be a transcription of Moti’s response, it is written: “This goes to No1 and No2 but Kuda… it” – the missing word or words likely the result of whoever transcribed Moti’s writing being unable to read them.

One interpretation of the letter is that Moti was allocating a portion of his earnings in Africhrome to Tagwirei, who was acting as a proxy for Mnangagwa and Chiwenga.

Moti told amaBhungane, “I can unequivocally state that nothing was paid to Mnangagwa or Chiwenga, as they held no interest in the Africhrome transaction”.

Dispute

Moti’s prison letters reflect an ongoing dispute between him and his politically connected Zimbabwean business partner Tagwirei over money, to the extent that he sought the intervention of Mnangagwa and Chiwenga.

At one stage he instructed his assistant to tell Chiwenga to put pressure on Tagwirei and tell him “to be honourable and pay his dues”.

Internal Moti Group correspondence concerning the dispute with Tagwirei suggests that Moti’s appeals to “Number One” and “Number Two” did not fall on deaf ears.

The two politicians appear to have been actively involved in brokering negotiations between Moti and Tagwirei and, in effect, helping Moti collect his debts.

According to an update from Kaka, a meeting was held with “No2 and Kuda” on 4 September after Tagwirei failed to meet an agreement to pay $10-million by 3 September.

Tagwirei again missed a deadline to pay the money and arrangements for him to pay “through bonds and later through police commissioner debt to him” came to nothing “despite sitting ins and discussions with No1 and No2”.

Moti’s associates kept up the pressure on Tagwirei through Mnangagwa and Chiwenga.

Kaka’s update continued: “Wednesday 19 September 2018, met with No1 who confirmed that he met with Kuda on Tuesday night… and undertook to pay the balance (making plans to organize the funds). No1 left for New York and said No2 will deal with the matter. Went to meet with No2 and said that he will follow up.”

Kaka told amaBhungane that, as a shareholder, Tagwirei had various financial obligations to ACF, which were managed by ACF and the Moti Group’s treasury department.

After Moti’s arrest, Kaka says he “was requested to approach [Tagwirei] to make payments in terms of his obligations”, and that because ACF had National Project status, he, Kaka, was responsible for reporting to President’s office (which included the Vice-President’s office) on the “financial status of ACF as a foreign direct investor”.

Tagwirei’s failure to pay on time meant further appeals to Chiwenga and a meeting between him and Kaka on 25 September.

Such disputes became a recurring theme in the relationship between Moti and his Zimbabwean partner, eliciting furious outbursts in Moti’s unfiltered letters. In one letter he referred to Tagwirei as a “black dog”.

Moti told us, “My relationship with Tagwirei is a commercial one which came into existence before he was sanctioned.”

The attempts to get Tagwirei to pay up proved exhausting, and in later letters, Moti continued to urge his employees to “push” Number One and Number Two on dealing with Kuda.

Pushing No1 & No2

From what amaBhungane has pieced together from Moti Group documents, Moti and his associates were able to convince the two most powerful men in Zimbabwe to personally attend to them on multiple occasions within one month alone, and there are other clues in Moti’s prison letters pointing to Mnangagwa and Chiwenga being personally involved in Moti Group business.

Often these are just vague or truncated sentences, such as a line in a letter to an associate at commodities giant Glencore in which Moti notes, “We on the game with No 1 etc”, or an instruction to “Push No1, No2 and Kuda. They must help us”.

Moti told us, “Again, it falls to me to remind you that you refused to provide me with the opportunity to authenticate any of the alleged documents… You should be reminded that there can be no legitimate means of acquiring these documents. Maybe you can explain why my constitutional right to privacy should be illegally breached to allow you to write a character assassination piece.”

At other times, Moti’s remarks are direct and specific, such as when Moti gave guidance to Kaka: “Get on the No1 good side Kaka. Cosy up to him. Explain to him that Kuda not being right and he is the only guy to tell Kuda to do right.” Or when he asked about “the claims No1 promised us? Are doing anything to push him Bro? ACF.”

Moti told us, “All the claims acquired by ACF were on sound commercial terms and legitimately bought. No party has ever “promised” or given ACF claims for free.”

The claims in question may refer to mining concessions known as special grants.

In a long 22 October 2018 letter to his team, Moti wrote: “We need to engage #1 and #2 and express our concerns with them so that between Kuda and No1 we need the govt now to allocate government grants as he promised us.”

In the letter, Moti articulated his preferred strategy for ACF not to “crowd” the Great Dyke – a geological feature where most of Zimbabwe’s chrome deposits are found – but to take over the area quietly to avoid others piling in and so as not to create “‘hype’ in the market as prices will go mad”.

The wording is somewhat ambiguous, but in essence, it appears that Moti intended to capitalise on the so-called “use it or lose it” policy that compelled holders of mining rights to exploit their concessions or risk losing them. The policy was supposed to prohibit the holding of mining titles for speculative purposes.

Moti would scoop up mining claims by getting Mnangagwa and Chiwenga “through ministry of mines to get claims and push the policy of [‘use or lose’] process’”.

The letter suggests that part of his strategy would involve the two senior politicians pressuring big companies into relinquishing claims, potentially by threatening them with the “use it or lose it” policy.

“Some of the people and companies mentioned are only accessible via No1,” Moti wrote, “Get an ‘in principle’ agreement with No1 and No2 and then this will further drive via MOM [Ministry of Mines] offices else you just wasting your time as the companies will want big money”.

Responding to amaBhungane, Kaka said that Mnangagwa’s government had a policy of promoting large-scale mining and resource exports. To do this, the Ministry of Mines, together with the President’s office, would “facilitate” the acquisition of claims by large companies “such that they could have larger tracts of land”.

“Accordingly, discussions in this regard took place in Zimbabwe, particularly in the mining industry, with much regularity with the government to boost the mining industry after Mugabe’s demise. Hence, there was no special treatment exclusive to ACF”.

Moti told us, “I would like to point out that requesting a politician to provide introductions between the sellers of possible claims and a company interested in buying these claims, is not illegal. The letter clearly instructs the company to attempt to purchase mining claims and try to avoid companies requesting inflated prices for their claims once they realise that a company is interested in purchasing claims.”

Greener pastures?

But, for all Moti’s political clout in Zimbabwe, all was not well and Moti’s business strategy in the country required him to navigate difficult factional terrain. His prison correspondence foreshadowed growing problems.

In October 2018, a letter from one of Moti’s employees stated: “Zim is not the same as you knew it. It will either settle or get worse. Relationships are changing and alliances are altering. Kuda under pressure… CDF [Chiwenga] is key to an extent but he is only back at work tomorrow for cabinet and back home. He is really ill. One and two not best of mates it seems too… noises.”

In January 2019, Moti was released from prison, but before the year was out, the Moti Group would temporarily halt operations and lay off workers at ACF amid a slump in the chrome price. Moti told media at the time that the “economic meltdown” in Zimbabwe made matters worse.

Perhaps emboldened by his efforts to cosy up to power in Zimbabwe, or because business in Zimbabwe was not working out so well, Moti turned his attention to neighbouring Botswana, where national elections were held in October 2019.

Internal Moti Group documents suggest that Moti had aimed to extract hugely favourable concessions from the Botswana state, grafting onto Botswana the sort of grand plans he had seemingly tried to set in motion in Zimbabwe years before.

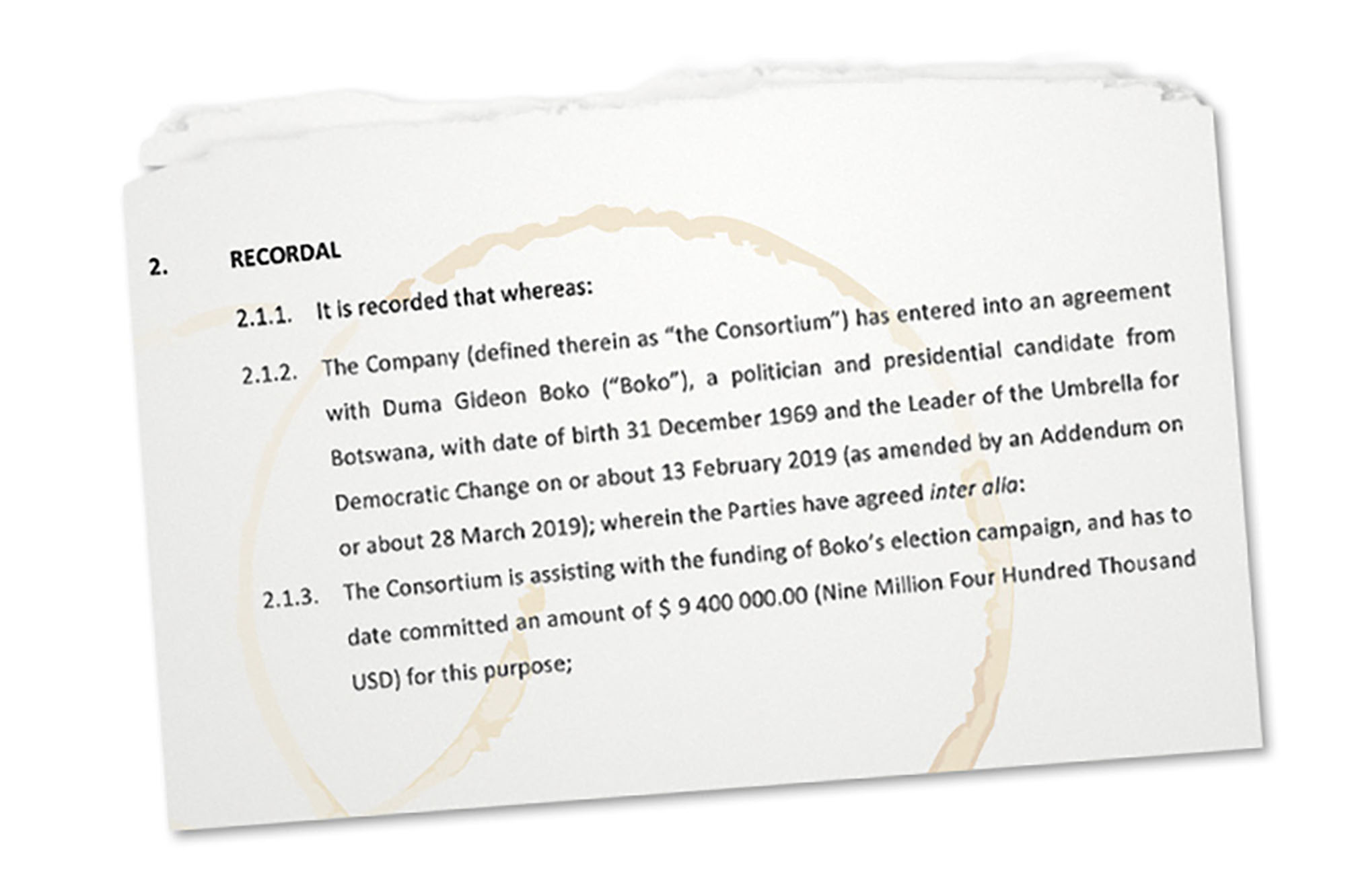

To do this, the documents suggest he was going to rely on the Botswana opposition as a Trojan horse, by backing Duma Boko’s Umbrella for Democratic Change.

Among the documents are ones purporting to show that a Moti company based in the Seychelles – called Longway Solutions – had entered into an agreement with Boko to fund his election campaign “and has to date committed an amount of $9 400 000. 00”.

In return, Longway expected “certain commercial opportunities with the co-operation and assistance of the Government of Botswana” in the event of Boko’s victory.

The eye-watering details of the expected opportunities included that the Moti group would be appointed to provide mandatory travel insurance to visitors of Botswana; be made chief negotiator to engage with De Beers diamond mining company, which plays a central role in Botswana’s economy; that the Moti Group would manage border control and security for the country, and undertake business activities in the beef, fuel, lithium and fertiliser sectors.

Relatedly, Exotic Holding Limited, a Moti Group company registered in the Seychelles, was to have exclusive rights to distribute generic medication in Botswana for ten years.

It is not clear whether Boko or the UDC had agreed to any of these plans, and he did not respond to the Sentry’s request for comment.

Moti told amaBhungane, “I did contribute a small amount to the UDC political party as they requested funding for their election campaign. As an investor in the SADC region, I am free to donate to a political party if I so wish, in the furtherance of the multiparty system of democracy.

“There is nothing wrong with acquiring fuel, lithium, fertilizer, or anything else commercially, and as a company we are more than entitled to do so. Our proposals were to add value to Botswana and would have been to their economy’s benefit.”

It was a bold gambit – sinking money into the opposition in the hope that should they come to power, the favours would flow back to Moti. But it failed to pay off.

The UDC did not unseat the incumbent Botswana Democratic Party, which won a crushing victory, taking over 50% of the vote.

Boko cried foul, with Moti again playing a supporting role by funding an investigation into allegations of electoral fraud by private investigator Paul O’Sullivan and a failed legal challenge. The allegations, however, came to naught.

Moti’s avenue to the Botswanan state was cut off, and he was never able to gain influence in that country the way he did in Zimbabwe. DM