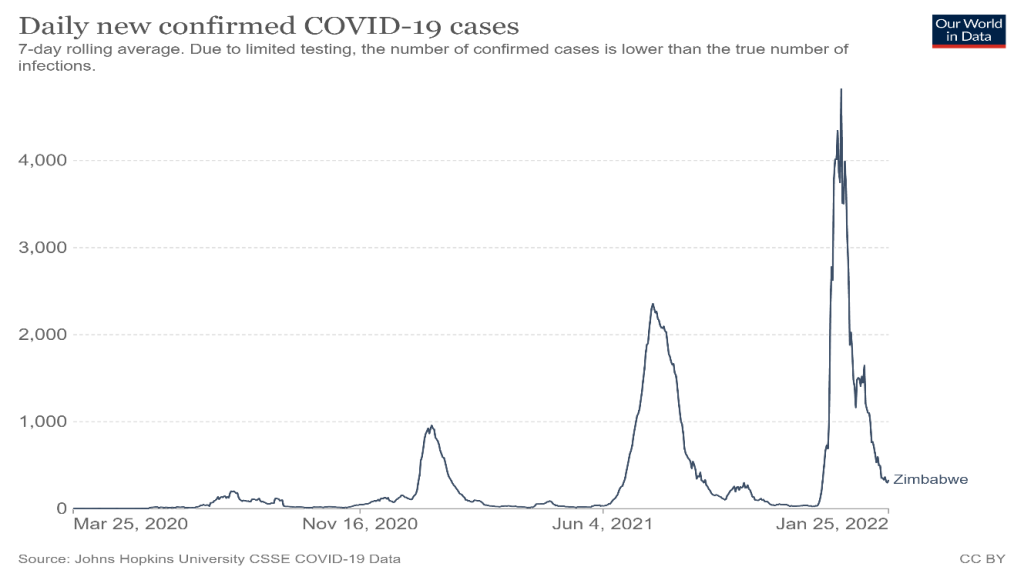

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 (the first case recorded in Zimbabwe was on 20 March 2020), health professionals in clinics and hospitals have been on the front-line of Zimbabwe’s response. In the last few weeks, while reengaging with our field sites, we have visited a number of health facilities in our rural study areas across Zimbabwe and talked to health workers about their experiences. As our informants explained, the three waves of the pandemic in Zimbabwe have been quite different.

The fear of COVID: the first wave

At the beginning of the first wave from late March 2020, there was a deep fear of the unknown. Health workers were confronting a novel virus without protective equipment and no known treatment or preventive vaccination. People watched TV and saw the scenes from China and then Europe, looking in horror at what might be coming their way. Much commentary saw the parlous state of health systems in Africa and feared the worst. Certainly, our informants reflected on how they were all initially terrified, sometimes avoiding seeing or treating people for fear of contracting the virus, while later they learned how to respond to the disease, but with significant wider challenges.

Across Zimbabwe, the first wave saw limited cases and few deaths, and these were nearly all imported cases with deaths recorded in hospitals in Harare. One nurse, now based in the Lowveld, experienced this first-hand as he was a student the main hospital in Harare at the time. With qualified doctors and nurses on strike, students were asked to attend the COVID wards. Lack of PPE and no knowledge of how to treat patients meant that they had to improvise. The lack of ventilators in the country meant that any escalation of the pandemic would have been disastrous. Luckily, this did not happen. Whether the strict containment measures enforced through a harsh lockdown helped or it was other factors at play, no one knows, but the first wave came and went with only limited impact. In our sites, clinics and hospitals instituted strict screening requirements for entry and with testing facilities emerging, there were requirements for widespread testing, especially of staff. This was initially resisted as everyone feared the virus. Being COVID positive was seen as a potential death sentence, and would result in enforced quarantining.

Tensions between public health measures and public views: dilemmas in the second wave

Vaccines became available from February 2021, but vaccination drives in our rural sites initially saw very limited uptake. Hesitancy emerged for a number of reasons. Low incidence meant that there didn’t seem a need. The misinformation from WhatsApp groups and social media was extreme, with all sorts dangers suggested from vaccination in general and from Chinese vaccines (the only ones initially available in Zimbabwe) in particular. Fears were also held by health workers, who were one of the first groups where vaccination was mandated. Many we interviewed admitted they delayed getting vaccinated until it was clear that the vaccines were safe. This made their role in promoting the vaccination drive somewhat ambivalent; although this changed as vaccines became more widely accepted. By the time of the second wave from mid-2021, when deaths and more serious illness were experienced, the demand for vaccination increased dramatically, as did the effectiveness of delivery and supply in the rural areas.

By this time, health workers across our sites felt more prepared. There was better protective equipment available as well as testing facilities, and they were more accepting of vaccination as a strategy. Health workers had also become more relaxed about regular testing, and saw this now as an important preventive measure, protecting them and their patients. In this wave dominated by the Delta variant, there was however some sickness and death across our sites; although it remained limited COVID was definitely much more present in the rural areas than during the first wave. Reflections from health workers on this period were more about how systems were developed to test, trace and contain the disease. Given the small number of cases, this seemed to be remarkably effective. Who knows if there were other unrecorded cases elsewhere, but it seems that the timing of the wave in the dry season helped limit spread. By this stage, the lockdowns were increasingly being challenged by locals, as they were affecting livelihoods and businesses seriously. Health workers commented on their importance for public health, but recognised the challenge of implementing them when there was actually so little recorded COVID around.

These tensions between public health recommendations – strictly following government (and in turn WHO) regulations – and the negative impacts on everyday life became increasingly evident, as all our informants acknowledged. Lockdowns also had negative effects on wider health care. Transport restrictions (combined with fear of testing and then getting isolated) meant that many didn’t come to clinics or hospitals at all, or only late. This meant that there was an increase in complications around pregnancy and births for example. Those preferring to treat COVID at home with the growing array of indigenous herbal medicines available may equally have risked late treatment of malaria, which COVID was confused with. This likely had fatal consequences. Some informants even suggested that, particularly by the time of the third wave, which came in the malarial wet season, malaria deaths probably far exceeded mortalities from COVID, and may well have been exacerbated by COVID measures as people were late to test and get treatment.

And then there were all the other knock-on consequences of the lockdowns and the disruption of the economy. Mental health was mentioned, including the problem of boredom of young people now unable to go to school. This resulted in increased substance abuse, as well as unwanted pregnancies amongst of very young girls. These wider health consequences of the pandemic (or at least the response to it) were mentioned frequently by health workers and villagers as major impacts (far more than the virus itself).

The emergence of a plural health system: the third wave

The third wave in December 2021-January 2022 was different again. As everyone recalled, Omicron presented as a bad ‘flu, but there were few hospitalisations (all from other conditions) and no directly attributable deaths. During this phase, the local treatments (steaming, herbal teas and other concoctions) had become part of daily life, for both treatment and prevention. These were seen as highly efficacious. Health workers admitted using them at home and with their families. Here the blurring between home life and treatment of health among the family and the official public health role became most apparent. As one nurse observed, I take off my uniform when I get home leave it until I go to work the next morning.

At home, health workers just like everyone else were engaging with a wider, plural health system, involving herbalists, healers, prophets, pastors, spirit mediums and traditional doctors, alongside their own medical training. In the context of the uncertainty of a new disease – and one that seemed to be so different in each wave – this made absolute sense, and none of our informants found this contradictory or problematic. To protect themselves and their families they would follow whatever worked, usually hedging bets given prevailing uncertainty. In the clinics and hospitals, the protocols had not changed much from the first wave. At the clinics, paracetamol was administered along with antibiotic injections for severe cases to reduce co-infections, but for Omicron a different regime was required, and local remedies served the purpose well.

All the health workers we talked to had worked incredibly hard during the pandemic. Unlike in other parts of the world they did not have to deal with the horrors of massive sickness burdens and death, but they had to follow a set of complex measures of testing, masking, distancing and so on that made their jobs more difficult. And, with limited facilities and initially barely any protective equipment, the fear and stress that the initial concerns about how the pandemic would play out took its toll. They had to deal with the dilemmas of advocating testing and vaccines that initially they had their own concerns about. And they had to convince a public to follow a whole panoply of public health regulations associated with the pandemic, while still coming to clinics or hospitals with regular diseases. Masking became widespread but restricting gatherings, particularly of churches and political gatherings was more difficult. And as time went on, especially in the hot season, masks became an additional garment hung around the chin, and quickly put up over the nose and mouth if a police officer was near or a roadblock was approached. Lockdowns as containment measures for a disease that was only sporadically present and at very low levels presented a dilemma for many we discussed with. While accepted at the beginning in the face of deep uncertainty, later many were more circumspect of their value. Lockdowns, for example, meant that patients presented late if at all, increasing the acuteness of conditions and resulting in different health burdens and more challenges for health care.

Everyone we talked to agreed that, with the pandemic changing in form and severity, opportunities to ‘live with virus’ were increasing and the costs of some of the remaining public health measures probably exceeded their current value. Many lessons have been learned about how to respond to a pandemic in a rural setting, and importantly how public health has to be balanced with livelihood and economic needs, while being supported by local approaches to health care and treatment as part of a plural system. These will be important as health systems prepare for the inevitable next pandemic.

This is the 20th blog in a series on the COVID-19 pandemic. Search COVID-19 for other posts. A full compilation and overview will be avialble soon. Thanks to the team from Chikombedzi, Wondedzo and Chatsworth and the doctors, nurses and environmental health technicians in the clinics/hospitals for sparing time to speak with us.

This blog was written by Ian Scoones and originally appeared on Zimbabweland