The Chronicle

Mashudu Netsianda in Zvishavane

DRIVEN by the desire to liberate the country from the yoke of colonialism, Cde Obert Matshalaga (71) together with about 400 learners from Manama Mission School in Matabeleland South province, trudged through the perilous bushes under the cover of darkness oblivious to the danger of being killed by Rhodesian soldiers.

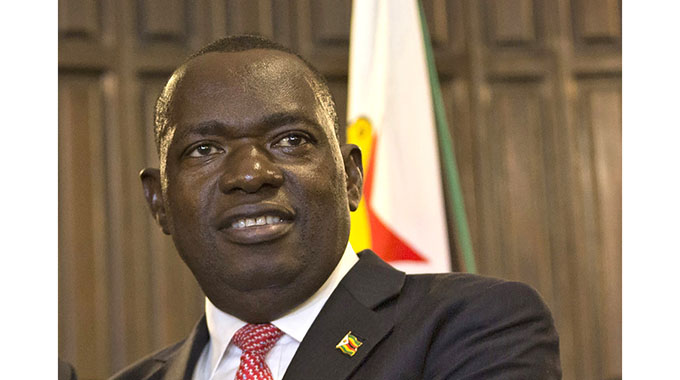

The late Minister of Foreign Affairs and International Relations Dr Sibusiso (SB) Moyo

The late Minister of Foreign Affairs and International Relations Dr Sibusiso (SB) MoyoIt was sometime in January 1977, a few days after the beginning of a new school term when Cde Matshalaga and his pupils under the stewardship of Zipra guerillas, crossed into Botswana through Shashe River to join the struggle.

The learners, among them the late Minister of Foreign Affairs and International Relations Dr Sibusiso (SB) Moyo; the recently declared national hero, Sampson Mpabanga; Elson Moyo, the Airforce of Zimbabwe Commander; Colonel Silibali Masera, Beitbridge East MP Cde Albert Nguluvhe and Zimbabwe Elections Commission (Zec) chief elections officer, Mr Utoile Silaigwana, had abandoned their evening studies to go for military training in Zambia via Botswana.

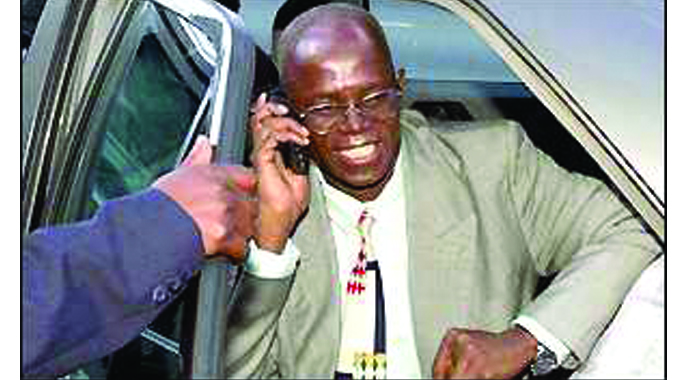

Cde Albert Nguluvhe

Cde Albert NguluvheCde Matshalaga who was the teacher on duty tasked with supervising the learners, decided to join his pupils in deserting the school just before nightfall on that particular day.

The Manama Mission incident was the most dramatic one in that the Rhodesian government alleged the learners were taken at gunpoint and force-marched to Botswana.

Those who are now in business who left Manama are Bester Dube, Naume Ncube Mthimkhulu, Ivan Bhebhe, Batetsi Noko, Rabson Tlou and Dr Robson Mutandi as well as Dr Pearson Sibanda.

“It was beginning of the term in January 1977 barely three days into a new school term. I was the teacher on duty meaning I was the overall supervisor at the school tasked with ensuring that both girls and boys stick to the operational standard activities,’ said Cde Matshalaga.

He said the learners were about to go for their evening studies when the bell rang.

“We rang the bell, which we normally did and the freedom fighters had timed that.

Manama High School

Manama High SchoolThere was commotion and I was still at my house and one of learners came running to me and shouted ‘kuyahanjwa baba’ meaning we have to go,” said Cde Matshalaga, who is serving as a Commissioner for the Zimbabwe Gender Commission.

“With my dirty clothes on, I immediately bolted out of my house and joined the learners numbering 400. The biggest fear was that during the day we had spotted Rhodesian soldiers patrolling the area.”

Cde Matshalaga said they started marching out of the school yard and headed towards Tuli River, which is about 2km away from the school.

“We crossed Tuli River whose water levels had subsided and got into an area called Mapate when it was just getting dark. The good thing was that there was moonlight hence we could see where we were going,” he said.

Along the way, they would get into stores they came across and liberally help themselves with whatever was in the shelves. Even some of the girls who were working at those shops took advantage and joined the struggle.

“We were now moving with our provisions from the shops that we looted. The situation was very dicey because we knew the Rhodesian security agents were in the area,” said Cde Matshalaga.

“The freedom fighters had carried their reconnaissance to time so that we were safe. The idea was that we should march across the Shashe River and get to Botswana before dawn and this was achieved,”

Rhodesian Air Force planes

Rhodesian Air Force planesHe said as soon as they crossed Shashe River, immediately the Rhodesian Air Force planes started circling in the sky and it was already dawn.

“The mood was electric and everybody was excited about going to war and some of the students were saying to me ‘we are now going to meet the people that you have always spoken about such as Cdes Nikita Mangena and Herbert Chitepo among others,” said Cde Matshalaga.

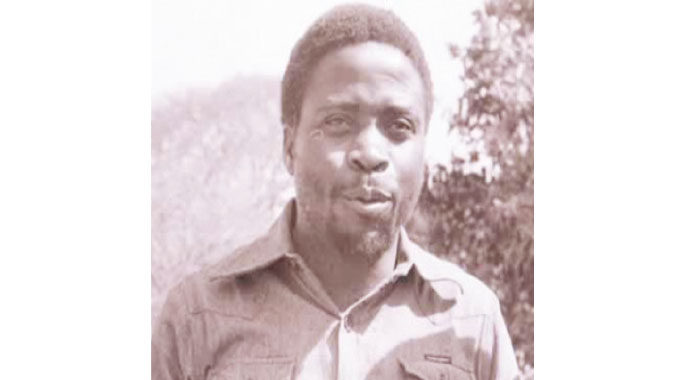

Cde Rodgers Alfred Nikita Mangena

Cde Rodgers Alfred Nikita Mangena“That was time when Cde JZ Moyo had already been killed. Some of the inquisitive learners were already asking ‘who are these people that you are talking about?’ I responded by saying these were people already in the struggle to liberate the country.”

Cde Matshalaga said there were liberation war radio stations in Maputo and Zambia and some of the students used to listen to those radio stations hence they were aware of the idea behind the liberation struggle.

“When we got into Gubajango village in Botswana, the people, particularly the chiefs, were very accommodative and forthcoming since the challenge that boggled our minds revolved around how we were going to feed all these learners,” he said.

The chiefs in Botswana organized food to be cooked for the group.

Cde Matshalaga said on that particular night it rained heavily for about two hours and they sought shelter in classrooms at a local school.

The following morning the Botswana Defence Forces and the police made arrangement for the group to be moved to another place.

“Since we were at a village, which could not sustain such a huge number of people, we were then taken to Bobonong and that is where they started screening us and writing our names and most of us gave pseudo names,” said Cde Matshalaga.

“Some of the learners had bruises and blisters because it was not easy walking such a long distance. We had had minimal training on survival, how to take a cover in the event of an attack and how to hide away from planes flying over us. Those who needed medical attention were assisted.”

He said there were others who could not make it after fainting and remained behind.

Cde Matshalaga said they were further driven to Francistown where there was a refugee camp.

“The parents of the learners thought their children had not voluntarily left the school. They reported the matter to the Rhodesian authorities and buses were organized to fetch us in Botswana, but few came back and most of the learners agreed to proceed with the journey,” he said.

“Most of the buses returned empty. The learners were already in the mood of joining the liberation struggle and they were determined.”

Upon arrival in Francistown, Botswana authorities gave them an option to either join ZIPRA or ZANLA and the majority of them went into the ZIPRA section of the camp.

“From there, they started airlifting us into Zambia and it was our first time to board a plane and we enjoyed. We arrived at Nampundwe transit camp in Zambia and the situation was tough. There was little food a lot of exercises and in the morning we had to wake up to do toyi toyi,” said Cde Matshalaga.

“We were there for about four weeks and the president of Zapu Dr Joshua Nkomo decided to see us as teachers and we were then interviewed. At that moment we had boys and girls together and the party decided that the girls should be taken to Victory Camp and boys remained.”

The late Dr Joshua Mqabuko Nkomo

The late Dr Joshua Mqabuko NkomoAt Nampundwe we were told not use our original names and were immediately given pseudo names so that in the event of being followed by the Rhodesians spies, they would not be able to recognize us.

“I was named Eric Dube but for some reason it didn’t stick much because I was a school instructor.

We were later taken to Zimbabwe House in Lusaka and the idea was to brief President Nkomo on the situation at home,” said Cde Matshalaga.

“Dr Nkomo said the since camp had children who could not be trained as soldiers, he suggested that schools should be established for both boys and girls.”

Cde Matshalaga was appointed director of education and manpower development and his task was to look at how schools could be established for those who could not undergo military training.

“We had Paulos Matshaka, one Mr Madonko and Lifael Nyanga. We started getting more teachers who were coming in. We were told not to expose children to books that had colonial stereotype and talked about the supremacy of whites,” he said.

“We crafted a curriculum on what to teach so that those entrusted with teaching knew what was required by the party. As director of education I was tasked with identifying areas that were critical for the independent Zimbabwe and to also identify people to be trained in various skills such as engineering, medicine and so on.”

At that particular moment, Cde Matshalaga said they were getting about 200 scholarships from the then East Germany, the USSR and Cuba.

“However, most of these people had come without academic papers and we were very innovative. Once we interviewed a candidate and established that he or she had passed, we would then issue them with either an O-level or A-level certificate to facilitate their training,” said Cde Matshalaga.

The late Chenjerai Hunzvi

The late Chenjerai Hunzvi“Most of these people went to those countries for further studies. Some of those people became medical doctors such as the late Chenjerai Hunzvi among others. In the transit camps it was no easy including at the schools, which we had established.”

Cde Matshalaga said sometime they would run out food with a few donors such as Unicef and the Lutheran World Federation chipping in with food and stationary.

He said a school was later established in Kafue, which trained secretaries.

“Because of the number of people, more departments were created such as that of agriculture which was aimed at training people on agriculture, department of social welfare which ensured that people were catered for including the health department which had two doctors,” said Cde Matshalaga.

@mashnets

Article Source: The Chronicle